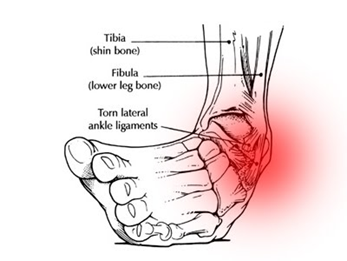

A twisted ankle is one of the most common injuries in sports and daily life, totalling between 3-5% of people attending UK emergency departments. The vast majority being Lateral Ankle Sprains (LAS), varying from minor stretching (Grade 1) as in most cases, to partial or complete ligament tears (Grade 2 or 3 respectively). It usually occurs with the sole of the foot turning inwards and ankle outwards, resulting in pain and some damage to the lateral ankle ligaments (see image).

Pain and swelling can inhibit weight-bearing and if you can’t walk a few strides, the early ruling out of a fracture is best done with professional medical advice or a trip to A&E.

Ligament tissue repair can take a few weeks to a few months, and sometimes full recovery takes up to a year. Most people (and coaches and sometimes medical staff) brush off an ankle sprain as a minor issue that doesn’t need treatment or rehabilitation, and go back to their sport or activity still with some swelling, pain, weakness or instability, with an ankle support or strapping.

Unfortunately, research has shown within 1 year, approximately 40% of first time Lateral Ankle Sprains go on to be a longer term Chronic Ankle Instability issue. And this has been implicated in later development of ankle osteoarthritis, and premature return to sport around 2-4 weeks may contribute to this with ligament healing occurring up to 12 weeks. See below for more on longer term (chronic) ankle instability.

There are a number of other chronic injuries that may be contributed to by repeated previous ankle sprains and resultant loss of dorsiflexion (ankle flexibility), like ankle impingement, or even issues further up the kinetic chain at the knee or hip (as my experience below). These are further reasons to ensure getting what may seem like a minor injury checked over, and the correct advice to improve recovery and reduce the chances of future issues.

So rehab is a good idea!

![PreHab Exercises - Compass Reaches for Hip, Foot and Ankle Activation and Stability]() Rehab

Rehab

The feeling of instability may be due to the damage and pain causing apprehension in movement, protective muscle spasm in the lower leg and disruption to the proprioception (or joint position sense) around the ankle. The main tools to aid recovery and strong tissue healing are initial rest and progressively more loading with strength and balance elements. These can develop from basic static exercises up to dynamic reactive (reaction to unpredictable movement), on to specific controlled sport or activity movements, and then more uncontrolled real life/sports movements, on the road to returning to where you were before. The basic principle of this is Mechanotherapy (and needs another blog to explain).

Finding ways to maintain fitness or skills base is also something a sports therapist can help with.

Manual Therapy

Early on to help ease any local muscle tightness or apprehension, particularly just prior to any exercise, some manual therapy such as soft tissue massage or mobilisation, or foam rolling and light stretching, may help improve ankle range of movement and allow more free movement during the rehab session. Once full range is reached later in recovery, this will probably not be beneficial.

Helping recovery and repair

Ensuring you get good sleep and nutrition will also help with repair and recovery. Try to adjust bedding to reduce pain and sleep disruption, and ensure an even ingestion of protein during the day. For more on recovery big winners and myths, see this blog.

Reduce re-injury risk

As stated above, the ligaments may still be repairing after you return to activity or sport, so an ankle brace or strapping during the first few months may help reduce the risk of recurrence and improve confidence in the ankle.

The likelihood of having another ankle sprain is increased if you have had one previously. For example in amateur and professional rugby, approximately a quarter of match and training sprains are recurrences, with similar figures for males and females. So continued maintenance of strength and balance/agility work will help reduce this risk. There are now a number or evidence-based injury reduction or ‘prehabilitation’ routines that can be added to weekly workouts or sport training warm up routines to help with this. Check out FIFA 11+ (Football), RFU Activate (Rugby) or Australian Netball Knee Program amongst other evidence-based ones freely available. (May need another blog for that too!).

Things that aid recovery and reduce risk of re-injury:

- Allowing and helping the tissue healing process to run its natural course.

- Progressively loading the ankle up to the demands of your activity or sport.

- Full adherence to the rehabilitation process and not stopping early.

- Inclusion of conditioning exercises in your routine to reduce future injury recurrence.

- A sport or activity specific warm up that prepares you (and in this case your ankles) for most movements you will encounter.

You may sprain your ankle again. These things happen in sport. However, the better prepared you are the less likely it will be and the quicker you will be able to recover afterwards.

My personal experience

From personal experience, I have had a number of ankle sprains through my sporting life since around the age of 18 up to now (33 years). On one side after a recent sprain, with feelings of ankle impingement and, due to the lack of ankle and knee flexion modifying movement patterns, I had reduced strength affecting lunging, deceleration and landing, causing left gluteal (buttock) and low back pain. All solved or managed with the above methods designed around my personal circumstances. This is now an ongoing part of my conditioning and much of it matches my sport conditioning program, so doesn’t take much extra time, effort or resources.

Some common myths to end on

1. Swelling is bad and needs to be controlled.

Swelling is a necessary part of the bodies healing process where in simple terms it helps protect the area and removal of damaged tissue. It may restrict ankle range of movement and alter joint mechanics so reducing swelling will help get the ankle moving normally again. Just need to let it run it’s course in the healing process. May need another blog!

2. My ligaments are permanently stretched and my ankle will always be weak.

There is some evidence that repeated ankle sprains cause some mechanical instability through ligament laxity. This feeling is also contributed to by functional instability through central changes in self-efficacy and sensorimotor control following traumatic injury. The resultant chronic instability may be expressed as instances of ‘giving way’ or further ankle sprains. The good news is this can be helped by a rehabilitation process building strength and confidence in the joint. The rehab process for chronic ankle instability is very similar to an acute ankle sprain and shows there are things you can do to help yourself.

I hope this has helped your understanding and inspired you to look after those ankles a bit more!

Happy exercising!

Lee